By Sarah Weld

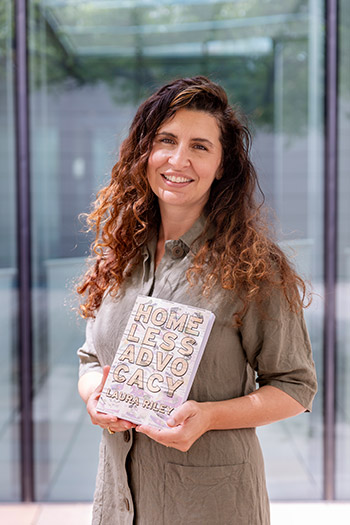

In Homeless Advocacy, her recently published book from Carolina Academic Press, Berkeley Law Clinical Program Director Laura Riley delves into how to be a legal advocate for people experiencing homelessness.

Aimed at anyone interested in working with unhoused populations — law students, policy makers, undergraduate and graduate social work students, and individual activists — the book includes a history of homelessness, insights from unhoused people, and their unique legal challenges.

Riley, the first person in the program’s inaugural director role, came to Berkeley in January from the University of Southern California Gould School of Law, where she was an associate professor of lawyering skills. The book draws on her work as a social justice attorney with experience in disability rights, women’s rights, and veterans law, when she often worked with unhoused people.

When she was a new attorney, she quickly realized there were few legal resources to consult for people like her — well educated in subject matter but not in how to represent people experiencing homelessness. This book is the resource she wished she’d had.

Q: You mention in your acknowledgements that the idea for this book sparked in spring 2020 just before the pandemic. What in particular inspired you?

Riley: I was overseeing field placements at USC and someone was teaching a course on homelessness for people doing public interest externships. We got to talking about how it’s important to have a pipeline of students who are familiar with issues that unhoused people experience. And we thought, there should be a book about this.

Q: Would you call it a textbook?

Riley: It is designed to be a textbook, and it’s through an academic press, but my hope is that people will read it outside of a classroom setting as well. I am hoping that activists or people interested in this deeply problematic societal issue can find the book accessible and have some insights around the legal side that they might not see in news coverage.

Q: Can you talk about your past legal experience, and how that helped inform your awareness and interest in this topic?

Riley: My initial exposure was in law school when I took a poverty law practicum. I wrote about the federal poverty line, and how it’s a wrongly designed measure for qualifying for benefits. Then in practice, I wasn’t necessarily experienced in working with people who were unhoused, and at each of my jobs a core set of my clients were unhoused or had housing insecurity.

For example, when I worked at the Disability Rights Legal Center some of my work was with cancer patients before the Affordable Care Act was enacted. These people couldn’t get health insurance because they had pre-existing conditions and they went into massive debt because of their medical bills. So all of a sudden people were housing insecure, and sometimes became unhoused because of their serious medical conditions. Then later I worked with female veterans who experienced military sexual trauma and other veterans with PTSD who did not have sufficiently coordinated support to secure affordable or subsidized housing.

Q: Who is the main audience for the book?

Riley: Current law students or practitioners who, like I was, are equipped in certain subject matter areas, but not necessarily in working with people who are unhoused. Many people in social justice or public interest jobs work with populations experiencing homelessness but don’t have any training on what that means, or what barriers clients encounter that are specific to their lack of shelter.

Q: Can you share some specific legal approaches that you have found successful?

Riley: The book introduces a range of advocacy approaches — some legal, some not necessarily — like legislative advocacy or litigation to get rid of anti-homeless ordinances or campaigns to keep criminal history out of job applications. But more important to me than pushing forward one method of advocacy or another was to introduce a range of what has been attempted so far, to inspire readers to build on those. And it was important to me to bring in voices of practitioners and also feature voices of people with lived experience of homelessness to speak to what did and did not work for them, because those voices rarely appear in legal texts.

Q: What do you wish people knew about those who are homeless?

Riley: The problem is not individual, it’s structural, and it’s many structures at work that go back for decades and even centuries. It’s important to look at the intersection of identities of the people who are experiencing homelessness in order to effectively work with them and represent them as attorneys. And then understanding that there are some foundational principles or ways to approach the work that can really help practitioners or advocates.

Q: What would you like to see cities, counties, and states doing differently?

Riley: Create housing. The central piece is to house people, and also figure out how to build sufficiently coordinated services to help people enter into housing and stay housed. So create housing for people, not just so-called affordable housing, which often is pretty limited, but housing that is completely subsidized. Housing, housing, housing.

And designing services so that there is access for people with different levels of exposure to technology, whose first language is not English, who might not feel safe entering certain spaces because of their gender or race, being aware of what access to supportive services means and coordinating that effectively. And doing an inventory of laws that criminalize people who are unhoused or understanding how the enforcement of certain laws particularly targets or impacts people who are unhoused.

Q: What is your wish for this book? And what are you hopeful about?

Riley: I hope that the book can be used as a tool for more people to develop courses around homelessness at the undergraduate and graduate levels. I also hope that people who are not going to take a course on homelessness can use it to inform their advocacy in their communities on behalf of either themselves or their clients. I’m hopeful that the foundational principles the book covers on housing first, trauma-informed care, and client-based advocacy can help guide practitioners’ approaches. These principles are becoming more known and that makes me really hopeful. Because if they’re becoming more known, then we’re practicing them more, and the more we practice them, the more we can figure out creative and new ways of employing them on behalf of and with people experiencing homelessness.

What also gives me hope are some of the people with lived experience that we included in the book. A lot of them have become advocates for their communities, and it’s really important that we work in community and with the community of people who have that experience.

Q: What do you most want readers to know about the book?

Riley: I really want people to feel like they can take this text and think of different and creative ways to advocate for and with people who experience homelessness, because we haven’t thought of everything. And we certainly haven’t implemented everything. So it’s a starting point.

The idea is to inspire people to think of their own possible solutions that might work in their communities. It could be on a really small town level, city level, county level, state level, or national level. Here are the skills that you can develop as an advocate. Here are the areas that would be helpful to be aware of if you’re going to be working in this area and in community with these populations. And here are some examples of things that worked and things that happened. And now what can you think of? Because that’s how advocacy works.